At any given SIHH or Baselworld, you’re obviously always going to see a plethora (to put it mildly) of new watches, but one thing you don’t see very often is a new escapement. That’s because designing a new escapement – much less one that can actually be produced in large enough numbers to be commercially viable – is probably the single biggest problem in watchmaking. Over the centuries since the very first – the verge escapement – was used in clocks, there have really been only a handful that have been used extensively, and in watchmaking, it’s a virtually certainty that any watch you buy is going to have a lever escapement. But not this one.

Omega now uses the Daniels co-axial escapement in all its in-house movements but it was a huge challenge for them to make it and enormously expensive in both time and money to industrialize, and departures from the lever in modern watchmaking tend to be made in very small numbers indeed (a couple of examples are the AP escapement, and the modern variations on the Breguet “natural” escapement, which you can read about here).

The Senfine (the name is Esperanto for “eternally”) is in a lot of ways not that different from a normal watch. There is a mainspring; the gear train is powered by winding up the spring, and at the end of the gear train is a mechanism that controls how fast the gears turn, and thus, how fast the hands move. But the parts that are different are very different. Just how much the Senfine departs from a conventional watch starts to become clear when you look at the numbers. The concept watch into which the Senfine movement has been built is roughly the size of an Omega Speedmaster, and yet, it has a power reserve of 70 days – not 70 hours, 70 days. The average balance wheel on a watch swings through a very wide arc – somewhere between, roughly, 260 to 320 degrees when a watch is lying flat. The balance wheel in the Senfine swings through only 16 degrees of arc. And, of course, with such a small swing, a higher frequency becomes possible: the version of the Senfine movement we saw has a frequency of an amazing 16 hertz, or 115,200 vph (as opposed to the 18,000 vph-28,000 vph range of most conventional watch movements, with high beat movements like the Zenith El Primero pushing it to 36,000 vph).

The escapement in the Senfine is an invention created by Pierre Genequand, an engineer on staff at CSEM (the Swiss Center for Electronics and Microtechnology). CSEM has been a partner with the watchmaking industry in creating next-generation silicon components, including the Girard Perregaux constant force escapement, and Patek Philippe’s Spiromax balance spring and Pulsomax escapement. Genequand began working on the escapement after his retirement in 2004, making a home-made working model in the corner of his kitchen. Eventually, he showed the model to his colleagues at CSEM, who decided to begin the long process of refining his design to see whether or not it could be made into a practical watch escapement.

For this phase of the escapement’s evolution, they partnered with Manufacture Vaucher, which creates movements for both Parmigiani Fleurier and Hermes, and which is owned by Hermes and the Sandoz Family Foundation. There were many obstacles that had to be overcome before a working prototype could be created – one of the most significant was that the escapement turned out to be very sensitive to shocks – but in 2014, the first prototype movement was shown, which had a ten day power reserve. Now, in 2016, the power reserve has increased to 70 days, largely thanks to the geometry of the escapement, which has extremely low power requirements.

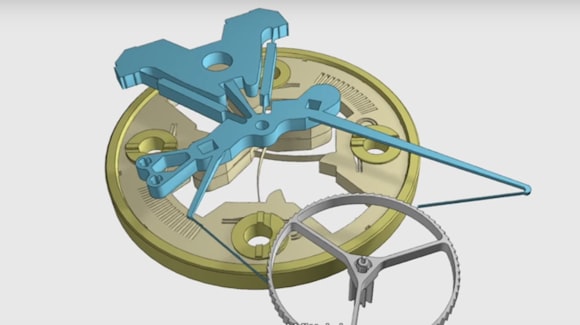

The escapement consists of an escape wheel with extremely small teeth, which like any escape wheel is propelled by the mainspring via the going train. The lever consists of two very long, thin, flexible pallets (the parts of the lever that actually make contact with the escape wheel teeth; in a normal watch, they're made of rubies) which just as in a normal lever escapement, alternately lock and unlock the escape wheel, controlling the rate at which the gears turn. This controls the speed at which the gears turn and thus, the speed at which the hands move.

The use of elastic components for the pallets is one of the key features that sets the Genequand escapement apart from a conventional lever. As you can see in the video below, produced by CSEM and Vaucher, the resulting high frequency but very low amplitude escapement allows for both high accuracy, and extreme efficiency.

One of the key features of the escapement, aside from its exotic geometry and flexibility, is the absence of a conventional balance staff. Normally, the balance wheel of a watch has a very thin central axis – the balance staff – made of steel running through its center, the pivots of which sit in two jeweled bearings, in which the balance staff and balance rotate. (If you drop a watch, one of the ways it can malfunction is for one of the pivots to bend or break.) The balance wheel of the Genequand escapement, however, is suspended by two flexible blade springs, which substitute for a conventional balance spring.

These flexible blade springs cross over each other and are attached, at the center of the balance wheel, to a block on which the lever sits. This construction means that there’s none of the friction you’d normally find at the contact points between the balance staff and the bearings – another important contributor to the lower energy costs of the Genequand escapement.

The Senfine prototype represents a really innovative use of silicon and microfabrication methods. In many cases, silicon in watchmaking is used to provide incremental improvments in existing technical solutions; the Genequand escapement shows what can be done if you start with a blank sheet of paper and work forward from there, bearing in mind the technical possibilities of silicon components. It also shows, however, that often in watchmaking independent research can lead to results that are parallel to the work of others – in this case, the Genequand escapement has certain technical similarities to, surprisingly enough, the grasshopper escapement, which John Harrison – the creator of the world’s first practical marine chronometer, in 1761. We’re told by Parmigiani Fleurier that Genequand was not actually aware of the grasshopper escapement during the development of the Genequand escapement, and there are obvious differences between the two designs. But the similarities are striking enough to lend credence to the old saying that great minds really do think alike – as you can see in the really fantastic animation created by YouTube's Ken Kuo below.

Over the next year or so, Parmigiani Fleurier and Vaucher will continue to refine the design; the next hurdle is that of temperature, as silicon’s elasticity is sensitive to temperature change. And we think Parmigiani Fleurier, Vaucher, CSEM, and of course, Pierre Genequand ought to be congratulated for taking things this far.

Silicon has enormous potential as an horological material, but it's always great to see it used to do something that really couldn't be done with other materials. We’re looking forward to the next chapter in this story, and finding out more about how this really ingenious, high frequency, low amplitude, lubrication-free escapement might eventually find its way onto your wrist.

Visit Parmigiani Fleurier online.

Follow HODINKEE's live SIHH 2016 updates here, and in our mobile app, and you can read all SIHH stories here.

No comments:

Post a Comment