One of the single most important features of watches intended to keep very accurate time is the presence of a stop seconds function. The single most important purpose of the tourbillon – as Breguet originally conceived it, certainly – is to make a watch more accurate. You would think therefore, in a rational universe, that you would see the tourbillon and a stop seconds function paired frequently, if not invariably . . . but you'd be wrong.

First of all, let's talk tourbillon. The basic idea behind the tourbillon is pretty simple: it's a solution to a really old problem in watchmaking, which is that a watch will run very slightly faster, or slower, depending on what position it's in. This is mostly due to how gravity pulls on the balance and balance spring in different positions. For example, think of the balance, which has at its center the balance staff (a very, very thin steel pivot). The tips of the balance staff sit inside the holes of two jewels, and when a watch is held in a vertical position, the sides of the balance staff pivots are pulled into contact with the edges of the jewels, creating a tiny bit of extra friction. It's not much, but it's still enough to change the rate of the watch, and affect accuracy. Getting a watch adjusted so that it runs at the same rate in both the vertical and flat positions is one of the basic problems in watch adjusting. If the vertical rate were always the same it would be an easy problem – you just adjust the horizontal rate to match the vertical rate; one way to do this is to slightly flatten the tips of the balance staff pivots, so you've got as much friction when the watch is lying flat as when it's held vertically. However, the vertical positions all differ slightly from each other as well – a watch usually runs, for instance, at a slightly different rate when the crown is up, as opposed to when the crown is down.

Thus, the tourbillon. The idea behind the tourbillon is to prevent the balance and spring from ever staying in any one position for very long. That way, you get a single average rate for all the vertical positions, which you can then adjust to match the flat/horizontal positions. As George Daniels says in Watchmaking (I'll paraphrase) you would now have a perfect timekeeper, were it not for the fact that aging oils change the rate of a watch over time. That was one of the main motivations for the invention of the co-axial escapement, but that's a story for another day.

The take-home for our purposes is this: a tourbillon's allegedly an aid to accuracy (there is some controversy about this, however) but at the same time, you can't easily set it to the second against a reference time signal, which really defeats the whole purpose of a tourbillon in the first place. For reasons I have to admit aren't entirely clear to me, nobody seems to have bothered to try to work out a solution to the problem of a stop seconds function in a tourbillon until very recently in horological history – 2008, in fact. That was the year that A. Lange & Söhne produced a really wonderful watch which is, alas, no longer in production, although they can occasionally be found at auction (and are very much worth snapping up if you can find one because they're historically important and, at least for certain tastes, phenomenally beautiful) – the Cabaret Tourbillon.

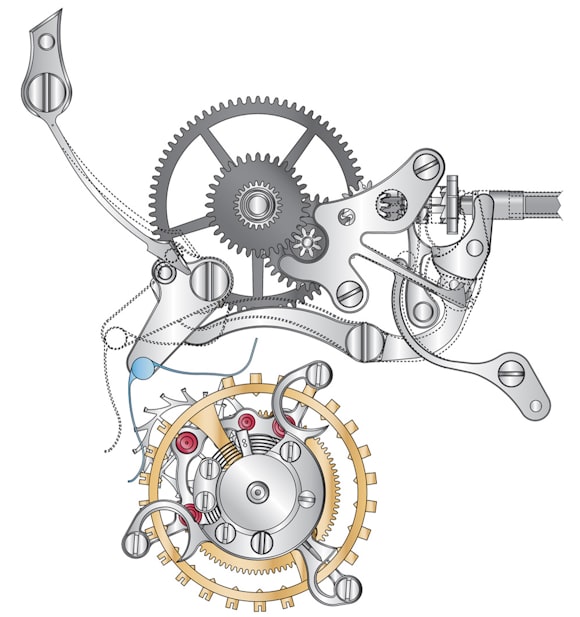

The Cabaret Tourbillon used a very interesting solution, and though the Cabaret Tourbillon is no longer part of the collection (though they do show up at auction) the mechanical solution is still used, in the 1815 Tourbillon – most recently, in the 1815 Handwerkskunst Limited Edition. When you pull out the crown, the stop lever moves into position just as it would on a non-tourbillon watch.

However in the 1815 Tourbillon, the lever is a Y-shaped, and pivots at the center so that even if one tip of the Y is blocked by a tourbillon carriage pillar, the other will still be able to descend and stop the balance (thereby stopping the movement of the carriage and the watch as well).

Another tourbillon with stop seconds that uses quite a unique solution (although when you talk about tourbillons with stop seconds, pretty much every solution is unique) comes from Moritz Grossmann; we visited their factory back in 2014 and were very impressed with what we saw. If you're not familiar with the company, they're an interesting story; based in Glashütte, they're a fairly new firm (founded by CEO Christine Hütter in 2008) with a very old name; Moritz Grossmann was one of the four "founding fathers" of watchmaking in Glashütte, the other three being F. A. Lange, Julius Assmann, and Adolf Schneider.

The Grossmann watch using a tourbillon with stop seconds is the Benu Tourbillon, which was launched by Grossmann in 2014. The Benu Tourbillon is a three minute flying tourbillon, which means you can't put a seconds hand directly on the tourbillon carriage (well, you can, but then you'll have a seconds hand that makes one rotation every 180 seconds). In the Benu Tourbillon the center seconds hand is out of the main power flow from the barrel to the tourbillon cage. The method of stopping the tourbillon is simple but clever: a tiny brush, made of human hair, forms the point of contact between the stop lever and the balance, and the tourbillon pillars are constructed in such a way that even if the brush makes contact with part of the cage, the hairs will simply part, allowing the brush to descend and make contact with the balance. (As we reported back in 2014, the hairs for the brush are actually those of CEO Christine Hütter – certainly an unusually literal interpretation, at least in horology, of putting something of yourself into your work.)

Another tourbillon with stop seconds is from the Grönefeld brothers, who make the Parallax Tourbillon (which we went hands-on with, not long ago). This is a technically interesting tourbillon on several counts. It's similar to the Benu in that both are flying tourbillons with center seconds; however the the Parallax is a one minute, rather than a three minute tourbillon. The Parallax is named for its use of a raised outer chapter ring that sits very close to the tip of the center seconds hand; the idea here is to eliminate parallax error in reading off the seconds.

The stop seconds mechanism here is a bit unusual. There is an indicator on the dial allowing you to see if the crown is in winding or setting mode; switching between the two is via pushing the crown in. When you enter setting mode, both the tourbillon cage and the seconds hand will continue to turn until the 12:00 position is reached by the seconds hand, at which point both the seconds hand and the tourbillon stop. The Grönefeld Parallax Tourbillon thus combines features of both the 1815 and the Grossmann tourbillons, but in its own idiosyncratic fashion.

Perhaps the most radical solution to the problem of integrating a stop seconds into a tourbillon movement is to do away with the problem of the cage, by simply doing away with the cage entirely. The Montblanc ExoTourbillon does just that. The ExoTourbillon is a tourbillon, but one in which the cage has been reduced to its bare minimum: a platform located just under the balance, which carries the escape wheel, balance and balance spring, and lever. The fact that there is no tourbillon cage means that you don't have to worry about the stop seconds lever striking one of the pillars of the cage – which means using a standard stop seconds solution presents no problem. The stop seconds mechanism can be found most recently in the Montblanc TimeWalker ExoTourbillon Minute Chronograph (above) and in the earlier Montblanc Heritage Chronométrie ExoTourbillon Minute Chronograph.

See the Montblanc Exotourbillon Rattrapante right here, and check out our hands-on with it here (no stop-seconds but well worth looking at). Visit Moritz Grossmann for a look at the Benu Tourbillon and if you're inclined, swing by Grönefeld for a closer look at the Parallax Tourbillon. And if you aren't already familiar with it, you owe yourself a visit to A. Lange & Söhne for a look at the 1815 Tourbillon.

No comments:

Post a Comment