The first time I saw a watch with silicon components in person was in 2003, when Ulysse Nardin's late managing director (and one of the lions of the fine watchmaking renaissance) Rolf Schnyder brought one to a collector's dinner hosted by what's now PuristsPro.com. The idea of silicon was fascinating and in retrospect, I think the fact that the earliest debut of silicon as a material in fine watchmaking was in such a revolutionary watch as the Freak did a lot to make the idea exciting rather than unsettling. But the adoption by none other than Patek Philippe – and then the assertion from the same company that it would make widespread use of silicon escape wheels, levers, and balance springs in almost all its production timepieces – raised a major question for many. At what point does a watch become a miracle of technology, rather than a celebration of craft? And can the two co-exist at all in the same watch?

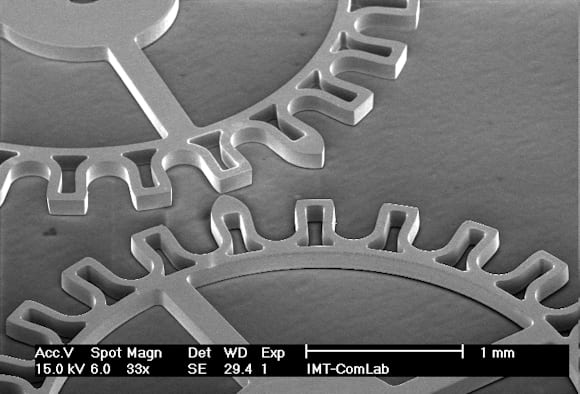

As silicon has become more ubiquitous, it's made it possible to pretty dramatically change what you get out of a watch; without it, and without manufacturing techniques like LIGA (a German acronym for Lithographie, Galvanoformung, Abformung – lithography, electroplating, and molding) a great deal of modern movement design would be impossible to realize. We looked just this week at the Chronergy Rolex escapement, but that's not an isolated development. Silicon escape wheels, balance springs, and levers, as well as the use of amagnetic alloys, have started a major shift in watchmaking towards very high resistance to magnetism becoming the norm, rather than something exceptional. Rolex, Omega, Patek, Seiko, and many other brands from low to high now routinely use exotic materials, and high-tech fabrication methods, to an extent nobody would have suspected when Ulysse Nardin launched the Freak.

Better resistance to magnetism, better rate stability, and greater efficiency in energy delivery to the balance are probably the three main basic benefits of all these high tech materials and methods, and they're all inarguably beneficial to consumers. And the diversity of approaches means watch buyers are spoiled for choice. But despite all that, I still find silicon hard to swallow, and so do other watch lovers, and I'm not entirely sure it's a rational decision. It's definitely true that silicon balance springs won't be replaceable if for some reason silicon fabrication becomes outdated, or we bomb ourselves back to the Stone Age (or the Iron Age at least, let's say) but short of imagining such post-apocalyptic scenarios, it's a little hard to take seriously the idea that no one's going to be able to make a silicon balance spring in a hundred years.

Silicon doesn't sit right with many of us, but the fact is, Nivarox balance springs are the result of highly technical industrial processes as well, and they certainly don't lend themselves to easy replacement by a lone watchmaker at his bench in some future scenario where making iron-nickel-beryllium-what have you balance spring alloys becomes a thing of the past. It is certainly true that in watchmaking, the inability to easily reproduce parts made of exotic materials, or with exotic methods, or both, can permanently turn a watch into an inert object; just ask anyone who's ever wanted an Accutron watch repaired. The problem there however, is not that we couldn't in principle make Accutron index wheels if we wanted to; the problem is that it's not worth it.

Watchmaking in general, as an industry, has been trying to get the man out of the loop as much as possible for centuries. You can probably point to the birth of the America watch industry as the real beginning; companies like Waltham took advantage of milling machines that had originally been invented for Federal armories in the 1820s in order to build factories capable of making half a million watches a year. The invention of alloys resistant to temperature variations for balance springs, the development of technology for making synthetic rubies, the development of technology for making synthetic oils in different grades, and a host of other technical advances mean that a modern watch – even the most "hand-made" – owes much, or most of its ability to function to technological and industrial processes that have very little to do with the pleasant idea of a watchmaker at his bench. So why does silicon feel so uncanny-valley to so many of us if it's just another chapter in the long history of trying to get reproducibly accurate watches made on any kind of scale?

The only answer I can think of is that a mechanical watch appeals very much because it's an inherently conservative object making use of an inherently conservative technology. You don't necessarily want the most pragmatically appealing technical solution. We all want different things from watches and for different reasons but what does matter to a lot of people is that a watch has some intangible ability to emotionally connect us to watchmaking tradition. And it's hard to think "silicon" without also thinking of microprocessors, and quartz resonators, and other nasty, modern, soulless things. Nivarox has been around for decades, and a Nivarox balance spring may be a high tech product too, but at least it's good old honest, you know, metal. I sort of hate to admit it but I have a purely irrational preference for Rolex's Parachrom over silicon – and I do mean irrational, it's not like a niobium-zirconium alloy is exactly artisinal watchmaking either.

I was actually horrified to hear that Patek was going all silicon for its balance springs (with the exception of certain high complications) and I don't know that I care for a LIGA-fabricated skeletonized escape wheel in my Grand Seikos either, but when I fell in love with watches none of those things existed and mechanical horology had been at a standstill since, probably, the 1960s. Is it really as irrational as that: that you tolerate only, and whatever, was around when you first got interested in watches? I'd be interested in hearing where readers draw the line.

No comments:

Post a Comment